Introduction

The higher education Law is in need of reform. This article argues for a new curriculum. In short, it should take a problem based,1 student centred, research based approach, supporting active, deep learning,2 and preparing students effectively for today’s competitive global market place. This is driven by the changing nature of legal education (which requires law degrees to be more profession facing), the changes to the legal services market nationally and internationally (with new benchmarks for qualifying law degrees), and the demands of cross border job opportunities.3

Therefore, the underlying academic ethos must combine academic rigour with legal practice skills, as required by the profession and the wider employability sector. It should provide a new learning culture, which treats learners as partners, problem solvers, and communicators. With an intake of high quality students, a Law school should be able to calibrate student learning at this higher level and help them to progress to a more confident, more employable, and highly skilled graduate.

Highlights of a new Curriculum

A good graduate of today and tomorrow displays more than excellent knowledge of the discipline. A good graduate must also display problem solving skills, robust and ongoing self-assessment skills, reasoning, excellent communication, and the ability to apply knowledge to new problems with the aim of solving them confidently. It is argued that there is urgency to develop a unique curriculum structure. For instance, there might be an education delivery through lectures, dedicated tutors, timetabled and facilitated learning groups, seminars, support material, formative (practice) opportunities, surgery sessions, peers from a higher year group, and electronic resources. Lecturers must expand from mere ‘disseminators’ to ‘facilitators’ focusing on deeper learning and practical application rather than repeating.4 Students must learn to self-assess, assess classmates, reflect on their own learning needs and group needs, and this way be involved constructively in the learning.5

Structure of a new Curriculum

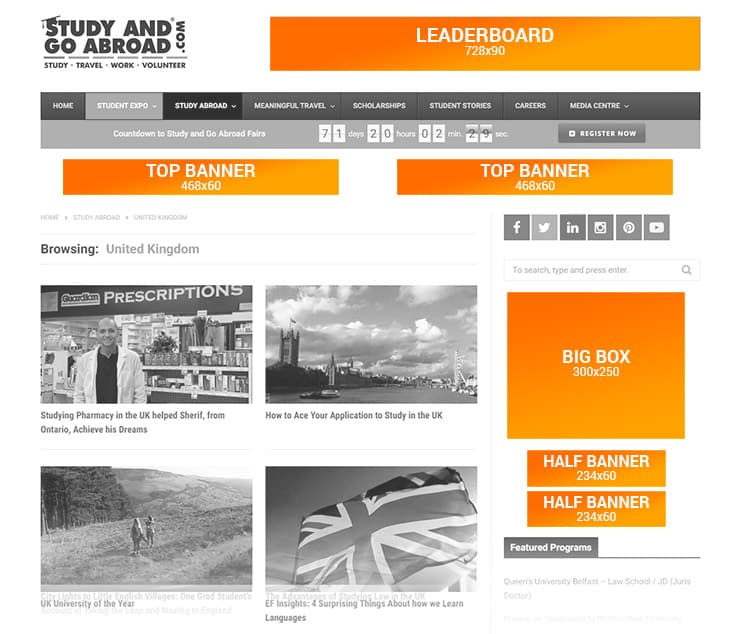

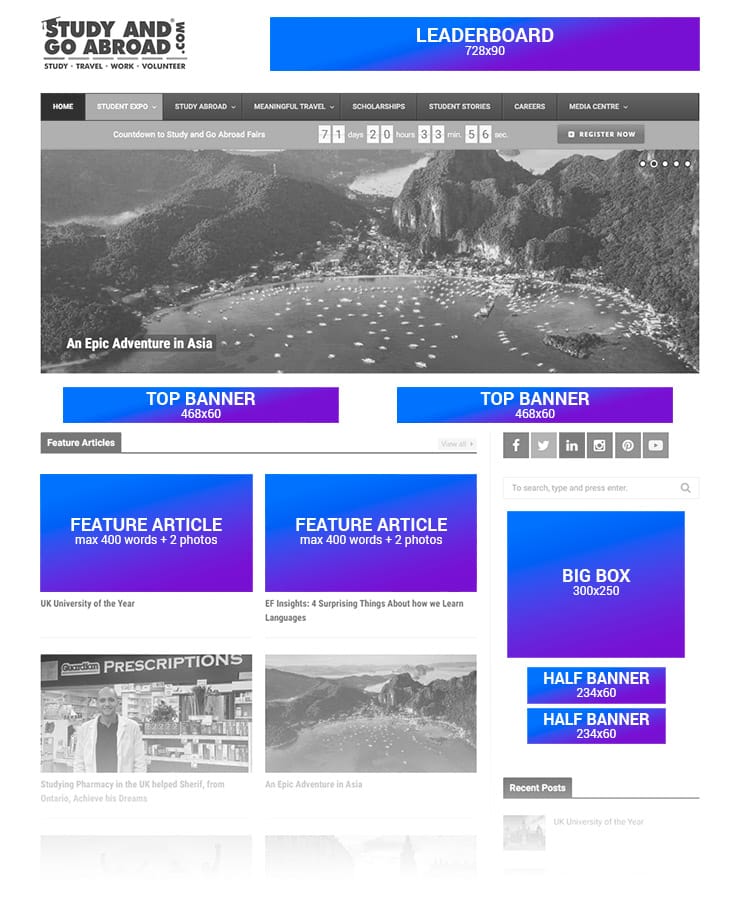

A curriculum must be designed to achieve enhanced ‘student centred learning’ (e.g. with fewer lectures and greater emphasis on individual and small group preparation), while providing enhanced academic support (e.g. doubling timetabled small group sessions).6 A suggested structure of such curriculum would be the following: The Year One cohort is divided into smaller learning groups – ideally timetabled – of up to twelve students. Students will attend a lecture on a topic and then convene as a learning group. The lecture will provide students with the knowledge and tools to tackle a legal problem. Students will then apply their knowledge to a real life problem in their small learning group, and through facilitated group work. This is followed by a seminar during which two learning groups come to together to solve a legal problem, directed by a lecturer. This learning cycle completes with a surgery which, rather than providing new information is an opportunity to clarify any outstanding questions on the topics covered. This structure of lecture-small learning group-seminar-surgery is offered fortnightly for each of the core modules, ensuring equivalency across these modules.7

Year One will form the basis for progression onto deeper skills and higher assessment in the years to follow. A variety of formative opportunities will help students refine their skills in a focused way. Through these formative opportunities students can easily identify their own learning needs, self-reflection and self-assessment, and the ability to think independently. There will then be progression into the higher levels of the programme, building and refining the skills acquired in Year One.8

Outcome of a new curriculum

This new engaging, student-centred, and problem-based approach will enhance students’ intrinsic interest in the subject matter, promoting deeper learning. Furthermore, students will develop and refine crucial skills such as communication, problem solving, and self-directed further study, ongoing reflection, and self-assessment. Achievement and progression will increase – as students develop their potential to the fullest. Upon graduation, students will have developed sophisticated problem solving skills, drawing on a deep and sustainable knowledge resource, which they have learnt to develop further independently, and communicating this knowledge effectively.9

Employability

Today a degree is no longer enough to guarantee a career.10 Besides disciplinary expertise, graduates from a reformed Law curriculum will be able to evidence additional graduate attributes, such as personal and intellectual autonomy – including deep and lifelong learning, effective communication, confident and effective problem solvers. This will help Law graduates to compete effectively in the global market place, making an impact and bringing with them the basis for a successful and fulfilled career, be it a law or non-law career.

Dr Greta Bosch,

Director of Education, Law School Exeter University, UK.

g.s.bosch@exeter.ac.uk

1 Problem based learning has been developed by medical schools in the US and Canada from the 1960s. It is an education and learning strategy that focuses around the solving of a problem through practical application of knowledge and skills. See: C E Engel, “Problem Based Learning” in K R Cox and C E Ewan (eds), The Medical Teacher (Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone, 1982), pp 94-101; M Gordon and K Winsor, Report on Problem Based Learning and its Relevance to the Practical Legal Training Course (Sydney: The College of Law, 1989).

2 For more detail on the difficulties associated with a teaching methods centered on lectures as a focus for transmitting knowledge, see: J. Biggs “Teaching for Better Learning” in Legal Education Review 2 (191), p. 138, and “Learning to Teach in Higher Education”, Routledge, London 1992.

3 See for example the Solicitor Regulation Authority UK consultation on ‘Training for Tomorrow: assessing competence’ in response to the 2013 report of the Legal Education and Training Review (LETR) in the UK, which called for a greater focus on regulatory attention on the standards required of solicitors both at qualification and on an ongoing basis. Start of the consultation was 7 December 2015, with an end date set as 4 March 2016. Part One of this consultation had been the development of a competence statement for solicitors. Or see the Bar Standards Board consultation, which closed in July 2015: This consultation focused on the Future Bar Training Programme, which looked at how education and training for the Bar can be made more consistent. As part of this a Professional Statement is being developed which will describe the knowledge, skills and attributes that all barristers should aim to have at the point of being issued a full practicing certificate. Part One of this Statement concerns the academic stage and in how far the academic state can contribute to the achievement of the BSB Professional Statement requirements.

4 Wood, S, Woywodt, A, Pugh M, Sampson, I, Madhavi, P. “Twelve Tips to revitalize problem-based learning”, in: Medical Teacher, August 2015, Vol 37, issue 8, pp. 723- 729.

5 Rue, J, Font, A, Cebrian, G, “Towards high-quality reflective learning amongst law undergraduate students: analyzing students’ reflective journals during a problem-based learning course”, in: ‘Quality in Higher Education, July 2013, Vol 19, issue 2, pp. 191-209.

6 Student centered learning has been defined as the learning through self-discovery under the supervision of a law teacher, see: Bee Chen Goh, “Some approaches to student centred learning in legal education, in: The Law Teacher 28 (1994), 159, cited in Baron, P, “Deep and Surface Learning: Can Teachers Really Control Student Approaches to learning in Law”, in: The Law Teacher, Vol. 36, Issue 2, 2002, pp. 123-139.

7 This is the approach Exeter University Law School takes: A fortnightly cycle of lecture, syndicate (timetabled small learning group of twelve students), seminar and surgery. Students sit in the same syndicate group across all four core modules in the year group.

8 For the importance of effective skills focused assessment and progression, see: Rigg, D, “Embedding Employability in Assessment: Searching for the Balance between Academic Learning and Skills Development in Law: a case study”, in: The Law Teacher, Volume 47, issue 3, 2013, p. 404.

9 Clough, J, Shorter, GW, “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Problem-based Learning as a Method of engaging Year One Law Students”, in “The Law Teacher”, issue 3, December 2015, pp. 277-302.

10 Bentley, D, Squelch, J, “Employer Perspectives on Essential Knowledge, Skills and Attributes for Law Graduates to Work in a Global Context” in: Legal Education Review, Vol. 24 Rev. 93, 2014, pp. 93 – 114.