Source: matadornetwork.com

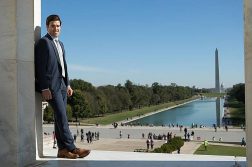

WHEN I SCROLL through James’ Facebook photos, I find an open door to places I am not — The Golden Gate Bridge, a small apartment in Marrakech, a street corner in Boston, an unidentifiable race track in the middle of sand hills, and a postcard-ready landmark in Paris. James, at 26 years-old, can lay claim to a berth of titles: he is an ex-school teacher, a book binder, a musician, a poet. His status updates read likes scraps of Jack Kerouac, Stephen Colbert, Johnny Cash, and The New Yorker. Above all, James is a traveler. He is studying the world. He is always, invariably, some place.

“Since last July I’ve lived in Rabat, Morocco; Miami, Florida; and Oakland, California. I leave Oakland at the end of the month for Miami then six months in Brazil,” James tells me casually. “I’ve frankly never considered not traveling. It’s how I was raised.”

The need to travel seems endemic to certain personality types. Sometimes we think of perpetual travelers — transients, gypsies, visitors — as merely those globetrotting in search of something that is missing in their lives. Though that may be true for some, a new study from the journal Intelligence highlights that there may be a distinct correlation between intellect and the compulsion to move. The study first aimed at identifying which geographical areas attracted the most intelligent populations, with the basic assumption being that smarter people with greater access to socio-economic resources would land in major cities.

Put simply: smart people move all the time. Psychologist Markus Jokela of the University of Helsinki found that cognitive ability, apart from income, played a significant part in American migration choices. The long-term study, conducted with a nationally representative sample over the years of 1979 to 1996, found that those who moved from more rural places to central cities scored higher on intelligence. Also, those who lived in a central city at the outset of the study and moved to the suburbs scored higher in intelligence than those who started in the city and stayed put. There were many variables involved in the study, but the one concrete take-away was this: folks with high cognitive percentiles tended not just to move to larger cities, but to move around more.

So maybe it takes a higher IQ to gain the temerity to pack all of your belongings in your humble apartment in Groton, Massachusetts (population 10,800) and head to a condo in Los Angeles (population 3.7 million). The world is so vast and our lifetime finite. Wouldn’t it be smarter (and therefore take a smarter person) to realize making the most of life, gaining the most knowledge, also meant continent-hopping and redefining home?

“There is definitely a charm to planting roots, but I fear my own complacency. You can’t be lazy when you have an expiration date. I have met so many wonderful people and I’ll miss my friends, but that’s the trade off — we die at the end of this and there is so much left to still see and learn,” James tells me. James’ words reminded me of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s, an expatriate himself: “With people like us our home is where we are not… No one person in the world is necessary to you or to me.”

The idea of wanderlust itself — the ravenous compulsion to travel and go and observe the world — is a loan word from Middle High German and closely associated to the Germanic system of apprenticeships. Journeyman, as they were called, completed training under a master and then spent typically three years wandering the earth, learning the craft of other masters, in pursuit of creating their own master work. Are James and his ilk looking to make their master work from airport to airport? Perhaps not, but part of the modern nomad’s journey is certainly about self-education.

One young woman in her late twenties, once a crew member on a luxury schooner, tells me, “I have been moving tons ever since I got out of [school]. I lived in Tortola in the British Virgin Islands, followed by Martha’s Vineyard, Vermont, Washington State, and now Providence.” Though traveling was an essential part of her career, I asked her why she feels the need to move — is it just about the job? “I feel like Goldilocks, but I kept moving wanting to learn about the country and also find a place to make my own. I think Providence will be home for a while, but I am not done moving in my life,” she says. Bob Roman, a key note speaker at 2012′s Ignite Phoenix, explains that everyone with wanderlust has at least a little of three characteristics: a sense of adventure, money, and good friends. While cash and a network are requisites, he also suggests that realizing that your life is not merely a drill is a major aspect of the modern nomad — and there comes the intelligence.

In 2014, wanderlust is not just for apprentices or travel-happy individuals; it’s becoming a brand. Travel literature constantly weaves its way onto the bestseller and classic lists — The Alchemist, Wild, and of course, On the Road. Elizabeth Gilbert’s perfectly boxed representation of moving to find oneself in Eat, Pray, Love glorified her hop from Italy to India to Indonesia.

Moving around is an expected part of modern life, a status marker — frequent flyer miles exist for a reason, and bands of Instagram accounts dedicated to travel logging have 35,000+ followers because they sell a desirable view of the world. Wanderlust — a folk-yoga festival established in 2009, has co-opted the name, even despite the fact that yoga is predicated on the belief in stillness. “A rolling stone gathers no moss,” and “not all who wander are lost,” read the trendy tattoos of Pinterest. The need to move might be as much of a natural compulsion as a cultural mandate.

One young pilot, an acquaintance, told me why he chose such a transient life. “There are hard causes like work relocation and roommate arrangements. Then we have the soft reasons, like personal fulfillment through uncertainty and the excitement of a new pursuit. Just have to peel away from what’s comfortable,” he explains.

Even if the moves consist of city-to-suburb or country-to-city jumps, roving has its way of seducing not only the boldest among us, but the most curious. Restless minds yearn for escape. “Traveling is a way to enhance perspective and combat anxiety, though I don’t imagine that holds for everyone,” James remarks, weeks away from moving cross-country. “It’s just hard to stop once you gain momentum.”